Ultius Blog

Overcoming Writer’s Block – Psychological Causes and Scientifically Proven Solutions

Writers everywhere are familiar with the phenomenon of writer’s block and the frustration that it inspires. Writer’s block is a slow in the creative process, when a writer fails to produce any new work of quality or, in some cases, anything at all. To combat this, ancient Greeks and Romans would seek inspiration from a muse. Others would pray for divine intervention to keep motivated. While most experience bouts of writer’s block that are limited to struggling to come up with original ideas, it is not unheard of for a writer, even very famous and successful ones, to battle with writer’s block for years at a time.

Even for all their success, world renowned writers like Stephen King and Samuel Taylor Coleridge had long periods devoid of productivity. History would suggest that no writer is immune.

While writers have likely been having trouble with writer’s block since man began writing, it did not become an actual, serious problem in the literary world until the early nineteenth century. During this time, writers began seeing their craft as something that was externally driven, inspired and fueled by some unseen force, rather than as a purposeful and logical practice. Poet Percy Shelley wrote in his private journal that, poetry was created from some kind of invisible influence that cannot be coaxed or controlled.

His thoughts would suggests that inspiration is something that a writer has to wait for rather than find within themselves. The idea that a writer has little control over their creativity and productivity is incredibly intimidating.

But are these writers actually physically unable to produce any work when they have writer’s block? Is there scientific evidence to support this halt in production? Or is writer’s block a crutch used by writers when they have been unable to perform well? This article will delve into the background and facts of writer’s block and discover whether the mental block is a real problem or merely an excuse. In addition, we will offer methods for battling your own writer’s block and suggestions for remaining productive.

First known cases of writer’s block

Though the term ‘writer’s block’ is something every modern academic writing student encounters, the phenomenon is much older. In his personal journal, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a renowned nineteenth century English poet, he vents his frustration over being unable to think of what to write. The majority of his works were completed while he was in his mid-twenties but had produced little since then beside literary critiques. In 1804, on his thirty second birthday, he wrote,

“Yesterday was my Birth Day. So completely has a whole year passed, with scarcely the fruits of a month.- O Sorrow and Shame… I have done nothing!”

His friends and colleagues expressed concern over his lack of production and questioned why he had stopped writing. Coleridge went on to complain about the remarks made by his fellows telling him to be more productive. He compared them to telling a paralyzed man to get up and start walking.

Writer’s block gains scientific attention

Writer’s block first received major professional attention in 1947 when psychoanalyst Edmund Bergler introduced the term. Due to its axiomatic quality, the term quickly became popular. According to the Comprehensive Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, Bergler described writer’s block as being complete or partial, and that,

“its earliest manifestation may be feelings of insecurity regarding one’s creativity, the development of a certain terseness of style, and looking to others for ideas for future projects”.

He believed that the underlying cause of writer’s block could be found in oral masochism and the super ego's inner need for punishment.

Is writer’s block strictly an American phenomenon?

Despite the first known case of writer’s block taking place in England, the idea of it seems to be seriously considered mostly within the United States. There is not a term for writer’s block in French or German. Modern day English writers tend to turn their noses up at the concept. Writer’s block has likely been around since man started writing, but even legendary Victorian authors didn’t have a name for the phenomenon.

In an interview with the Paris Review, English writer and composer Anthony Burgess has stated that he neither understands nor experiences it. He believes that those who have trouble with writer’s block must have the good fortune of not relying on their writing to provide a living to afford the luxury of waiting around to be inspired.

Famous authors who experienced writer’s block

Truman Capote

Even the most talented writers can suffer from writer’s block. Truman Capote was once a well-loved member of high society and is still renowned all over the world for his literary works. However, the publication of several of his pieces in Esquire magazine painted some of his high-powered friends in an unflattering light, exposing their secrets through thinly veiled characters and accusations of everything from gold-digging to murder, causing a scandal and his banishment from the upper crust of society

Many believe that this led Capote to have a mental breakdown and caused him to contact a serious case of writer’s block. For the last ten years of his life, Capote often spoke about a novel he was writing that would transcend all his other works. When he died, however, it quickly became clear that there was never any novel at all.

In a review of Capote’s work, it was speculated that the pressure to perform well, especially after his social scandal, paired with his mental breakdown, afforded him a serious case of writer’s block that he just simply could not shake. It is believed that this shame of being unable to write to his regular standard motivated Capote to lie to his friends and colleagues for an entire decade.

Stephen King

Even the eminent Stephen King was known to struggle with writer’s block. Though it seems hard to believe, and did not happen very often, he still occasionally had trouble being as productive as he usually was. In an editorial that he wrote for the Washington Post in 2006, King admitted that there were sometimes stretches of weeks and sometimes months when he was unable to produce any work at all.

He explained that he believes that writers tend to sabotage themselves without being conscience it, restricting their scope of imagination and therefore prolonging the blockage. He noted in his book, On Writing, that during one particular bout of writer’s block while he was in college, he did nothing for months with the exception of drinking beer and watching daytime television. Though certainly not as drawn out as other writers’ experiences with writer’s block, King’s struggles remind writers that even the best are not immune to the dreaded writer’s block.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

F. Scott Fitzgerald is recognized as one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century. He still receives acclaim today for his work, The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald was often inspired by events that occurred around him in his own life primarily during the jazz age of the roaring 20’s. To this day, The Great Gatsby is regarded as an American Classic Novel.

In the late 1920’s Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda was diagnosed with schizophrenia. It is believed this is when Fitzgerald began suffering from writer’s block. He fell into a deep depression and struggled with alcoholism.

In 1937 Fitzgerald decided to move Zelda into a hospital in North Carolina, and he himself moved to Hollywood to try to become a screenwriter in the growing film industry. While working in Hollywood, he began to produce the novel The Love of the Last Tycoon, but suffered a fatal heart-attack before it was completed.

Ralph Ellison

Another well-regarded writer who was known to experience a chronic case of writer’s block was Ralph Ellison. What makes Ellison’s writer’s block different from other cases was that he was able to write, just unable to write anything he was satisfied with. Ellison’s biographer notes that the classic writer held himself to incredibly, and sometimes impossibly high standards and would refuse to submit any work that he felt did not meet them.

His novel, Invisible Man, was published in 1952. Between the novel’s release and his death in 1994, Ellison collected approximately two thousand pages of notes for a second novel. Ellison had been asserting for years that the novel he’d been working on was nearly finished, but he was not yet satisfied enough to send the book into publishing, and ultimately never completed.

Henry Roth

Writer Henry Roth experienced one of the most famous cases of crippling writer’s block in modern literature. Though his book, Call it Sleep, was not initially popular when it was originally published, its re-release in 1964 climbed to much more success.

In the almost three decades that followed, Roth was unable to publish anything at all. The cause of his extended case of writer’s block remains unknown. Fortunately for Roth, his writer’s block did not last forever. During the 1990s, Roth published several volumes of Mercy of a Rude Stream, his widely regarded epic saga.

Causes of writer’s block

Problems in creativity

There are several suspected causes of writer’s block. Generally, writer’s block is perceived as a creative problem. Perhaps a writer may be having trouble finding inspiration and original ideas. Almost all writers have experienced this kind of writer’s block, and while frustrating, it is the easiest to overcome for most. For some, it can be speculated they simply didn’t have access to, or knowledge of resources that could help them overcome any difficulties they encountered while writing.

Another cause of writer’s block can be unfortunate circumstances in the writer’s personal life. This can include things every person experiences at some point, such as

- Illness

- Depression

- A failed relationship

- Financial troubles

As mentioned earlier, examples of this are present, as when Truman Capote suffered a decade-long case of writer’s block when he was cast out from high society. Such a major and devastating life change rendered him unable to produce any quality work. Another example is when F. Scott Fitzgerald contracted a case of writer’s block due to the declining mental health of his wife.

Similarly, the pressure to produce work itself can contribute to writer’s block immensely. Many famous writers report experiencing great anxiety from the pressure to write well, especially after finding success in previous acclaimed works.

Stress

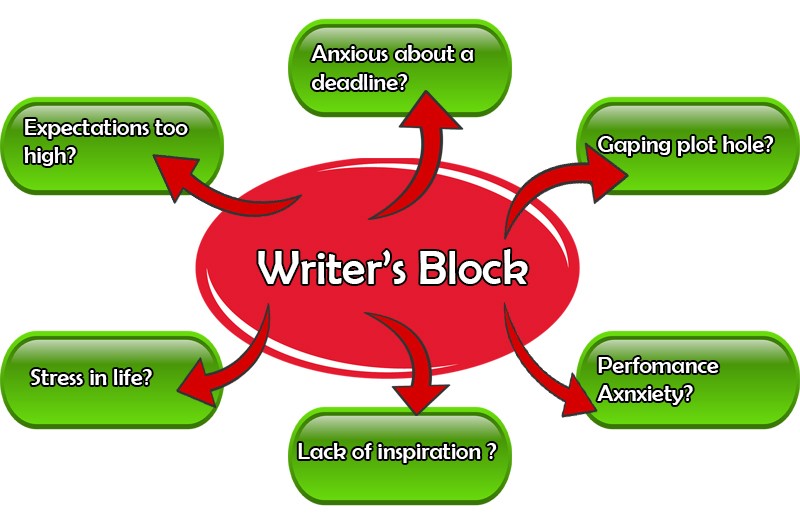

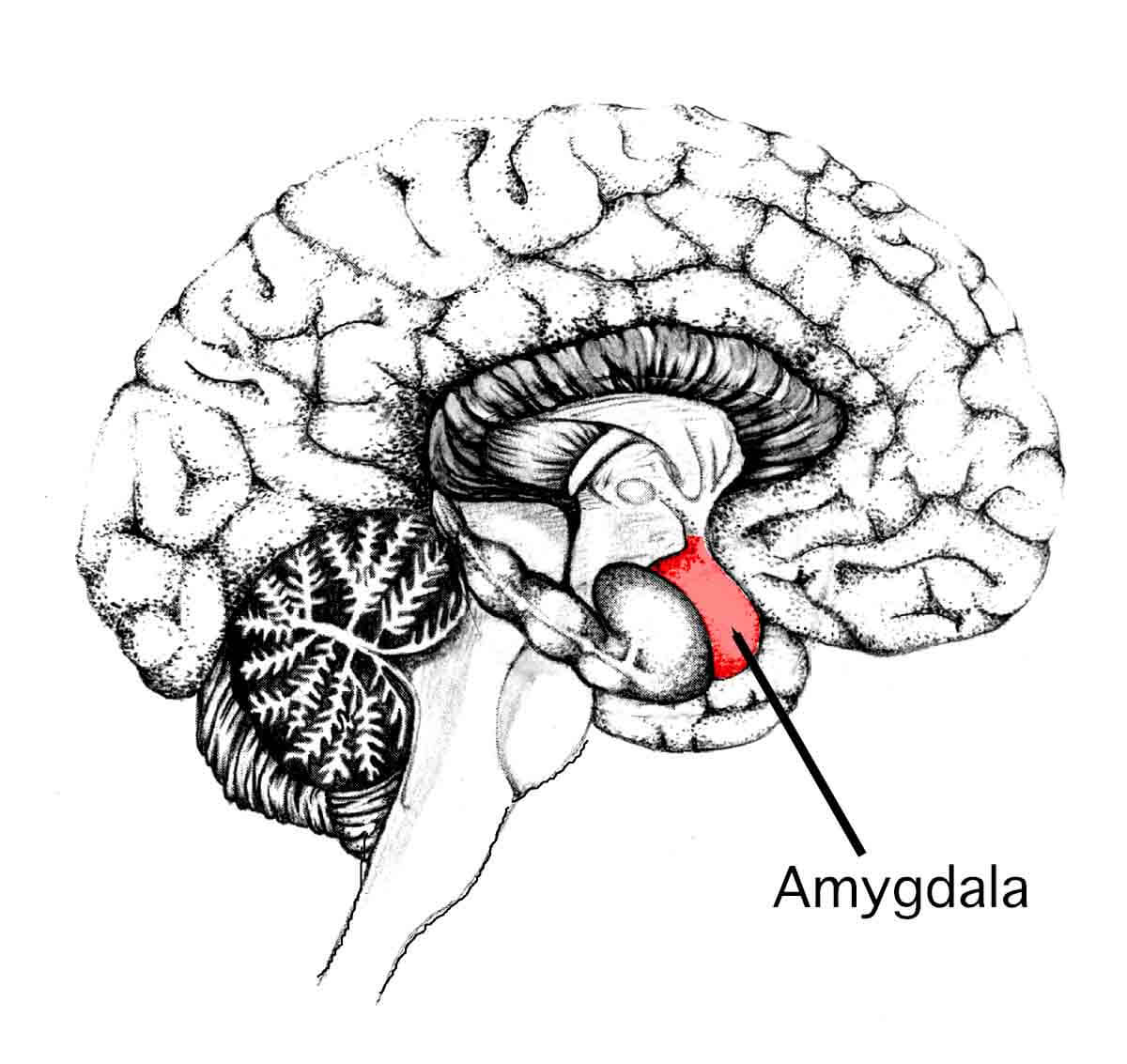

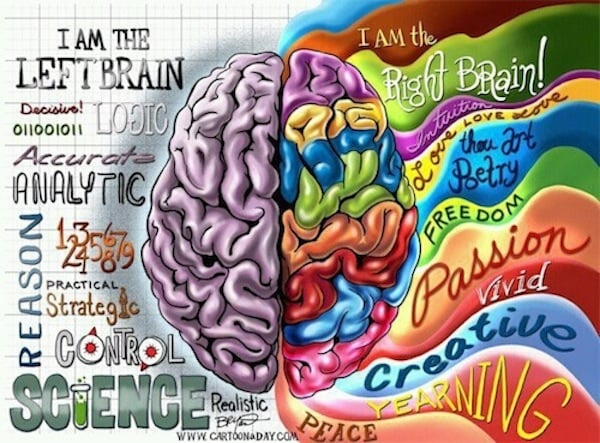

Other theories are a bit more scientific. Writer’s block can be considered to be a form of stress and the cause may lie in our brain chemistry. A study done by Texas A&M University observed the brain’s reaction to several stressful situations. According to the study, when under stress, control is shifted to the limbic system from the cerebral cortex.

With the limbic system is in control, our behavior is much more instinctual and locked in a fight-or-flight mentality. The lack in support from the cerebral cortex leaves one incapable of creative thought. When the change hits them, they respond with the limbic system’s instinctual reactions; first, the writer freezes and is struck with a momentary paralysis and second, they are suddenly choosing between fighting or fleeing. Writers are often unaware of this shift within their brains and instead attribute their struggle to a lack of determination or skill when in reality, their cerebral cortex is simply unavailable.

Fixation

Types of fixation that lead to writer’s block

Often times, when writer’s block occurs, a writer is fixated on one thought or idea that is either unoriginal or unfruitful, making it difficult for them to move past the block. According to a study done by psychology professor Steven Smith of Texas A&M, there are two types of fixation: functional fixedness and mental set.

Mental set is much easier to recognize and take control of. Mental set can be demonstrated in an experiment where a group of subject are given a list of ten puzzles to complete. The first nine puzzles are all solved with the same method but the tenth, though much easier to complete than the others, requires a different method. The presentation of the tenth problem will cause a mental block. So if a writer is detailing a flashback to an accident and then the story changes to a more descriptive tone, the writer may hit a block in an attempt to flip gears.

| Mental set | Functional fixedness |

| Approaching problems in only one way | Inability to see new uses for objects |

| Uses methods that are familiar | Inhibits creativity |

| Inflexible | Inflexible |

| Example: a child goes through a push door and then pushes on all doors, expecting them to open | Example: overcoming functional fixedness would be looking at a coin as more than currency and using it to tighten a screw |

If the type of fixation a writer is experiencing is functional fixedness, though, the solution is not as simple. Functional fixedness has more to do with our long-term knowledge and understanding than mental set does. Steven Smith demonstrated functional fixedness by asking subjects to draw a picture of a life form from another planet. While most pictures were different from humans because they had extra eyes or antennae, the figures were still human-like for the most part.

It did not occur to anyone that an alien life may take some other form, such as a cloud or light. Smith adds,

“One of the most insidious things about getting stuck is that it’s often because you’re making assumptions that you don’t realize you’ve been making... You don’t realize you put constraints on an idea that don’t have to be there. It’s only when you step back that you realize that, whether it has six legs or no legs, it’s still basically a dog.”

You may think that by adding extra body parts that you are being creative and original, but often times we do not realize how much further we can really push the boundaries of our writing.

How to combat writer’s block

Understanding the symptoms

Writer’s block can manifest itself at different stages of writing. Some writers have trouble just getting started, while for others, it’s coming up with a satisfying ending. It’s important to recognize the symptoms of writer’s block, and to try to prevent them whenever possible. The Purdue Online Writing Lab indicates that, for many students, writer’s block occurs when the student is assigned to write about a topic they have no interest in.

In this instance, it may be helpful for a student to focus on a particular section of the assignment to start with, that may be more interesting that the overall subject, and fill in the rest afterwards. If a student is assigned a subject they may not be familiar with, the student be scared to ask an instructor, or a tutor for more information, or ask to be pointed in a particular direction before they begin writing.

Understanding creativity

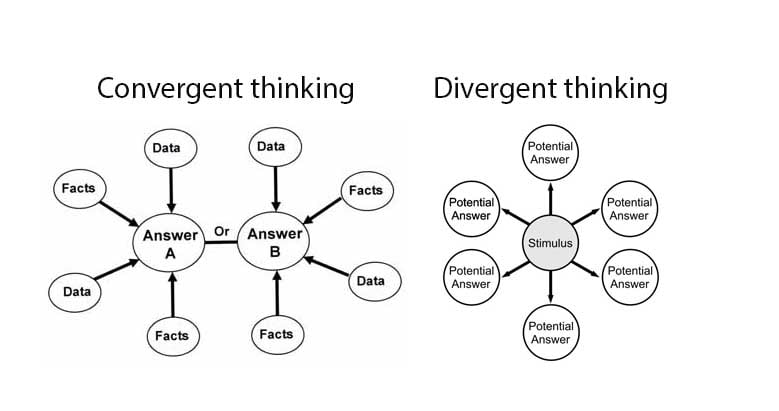

In combating writer’s block, it can be helpful to fully understand the concept of creativity. Psychologist J.O.Guilford created a creativity model in the early 1950s that breaks creativity down into two separate parts. According to the study, published in the American Psychologist Journal, divergent thinking, much like drafting a literary piece, is coming up with ideas and storylines that you might follow and seeing how the pieces might fit together.

The second kind of thinking, convergent thinking, similar to editing your drafted piece, is whittling your ideas down to one, meaningful path. Divergent thinking must be completed before convergent thinking can be effective and successful, but both are required to properly develop as a fruitful writer.

The blocks tend to occur during the divergent thinking phase. This is the part where the ideas must flow freely so they can be refined into something workable. Guilford’s model of creativity composes divergent thinking of three ingredients:

- One’s volume of ideas

- The variety of those ideas

- The originality of those ideas

In order to combat writer’s block, you must first determine where your divergent thinking is lacking. One way to do so, as suggested by The Literary World Journal, is to first spend one session of coming up with writing ideas and only worry about the volume of your ideas. The next session should be spent trying to list more varied ideas, making sure each one is different and independent from the last.

The last session should revolve around originality, and should consist of listing only ideas that are original and truly inspired. The session that generates the least amount of work should then highlight the area of divergent thinking that needs the most work and should be focused on the most.

| Divergent thinking | Convergent thinking |

| Generate new thoughts | Rate by criteria |

| Enhance pre-existing ideas | Decide |

| Widen perspective | Categorize |

| Combine/integrate | Connect |

| Engage possibilities | Employ guidelines |

| Explore the unusual | Clarify |

| Imagine | Focus |

| Visualize | Refine |

| Deter judgement | Use discernment |

Fighting fixation

When it comes to Steven Smith’s breakdown of fixation, there are several suggestions for either avoiding or fighting writer’s block. He states that is depends on the kind of fixation the writer is experiencing. If the fixation is mental, where your mind is set in doing something a certain way you’re not satisfied with, then the problem is not too difficult to overcome.

An easy way to combat this is to simply continue writing similar parts of the story for that writing session. Your work does not have to be read in the order it was written. That way, your mind can continue along the path it is running and you do not need to waste time trying to change gears.

If a writer is experiencing functional fixedness, the solution is a bit more complicated. Moving across the conceptual spectrum is difficult for many writers (even ones that write for Ultius), and Smith warns against falling into premature conceptualization. When this happens, writers move on to convergent thinking before they have even completed the divergent thinking phase.

In order to exercise one’s ability to think divergently, experimentation is key. It can be helpful to write a short piece with the only goal being to challenge every assumption. Though this will likely be difficult at first, it can be very helpful in recognizing your own visionary weaknesses as a writer, and help strengthen your ability to push the boundaries of conception. Those who manage to achieve this are able to write with more variability and with more originality than those who remain limited by their own conceptions.

Help from professors

While it is clearly helpful for writers to understand the scientific process within the inner working of our brains in regards to writer’s block, it can also be incredibly helpful for teachers and professors to understand how it works as well. When they are able to break it down and understand what is really happening in a student’s brain when they are experiencing writer’s block, they are better able to combat that issue before it affects the student’s writing.

In his article in the Journal of Reading, Lawrence J. Oliver Jr. stressed the importance of educators’ understanding the science of writer’s block and helping students to overcome the issues it presents. He feels that students do not receive enough advice on ways to improve their writing, and generate more ideas and expand their conceptual horizons and are forced to just push forward with the writing process, despite a lack of guidance. Students often do not receive any feedback or counsel until after the essay is done and the project is over.

The stress and insecurity of not having enough direction and being unable to easily produce original ideas can cause the shift in control from the cerebral cortex to the limbic system that attributes to writer’s block. What is even worse, is that the stress of a continuing bout of writer’s block can cause more stress, increasing the reaction that is causing the block in the first place, therefore creating a repetitive cycle. If teachers and professors were more aware of the scientific cause of writer’s block, they would be better prepared to help their students push through these difficulties and ultimately become better writers.

A case of unrealistic expectations

A study done by the Canadian Family Physician Journal sought to discover the causes and treatment of writer’s block. Researchers found that the creative block is oftentimes stemming from unrealistic expectations. These expectations are usually about how much can be written in a single sitting, or the belief that the first draft of a writing piece should be perfect. In order to combat this, the study concluded that it could be helpful to not only allow yourself to be imperfect, but to break down the writing job into workable pieces.

By giving yourself the proper conditions under which to work, you will be able to maximize your efficiency. Separate yourself from the things that are distracting you in order to sharpen your focus. Even playing soft music in the background can help you remain upbeat and positive about the process. Ensuring you have the proper work environment is a huge part of being productive. In a previous blog from Ultius, we discussed some other helpful tips for student writers.

The study also assessed more serious kinds of blockage. It is not uncommon for writers to question their abilities under the pressure of being unproductive. Researchers suggest that imagining you are someone else while you are writing, perhaps a writer you admire, can be helpful in increasing productivity. This works by inspiring you to go about the project as you believe they would. Another helpful suggestion would be to talk through your work either aloud to yourself or with a sympathetic ear, perhaps a friend or family member. Hearing your ideas out loud and being able to receive objective feedback from an outside source can be very successful in helping to develop your piece.

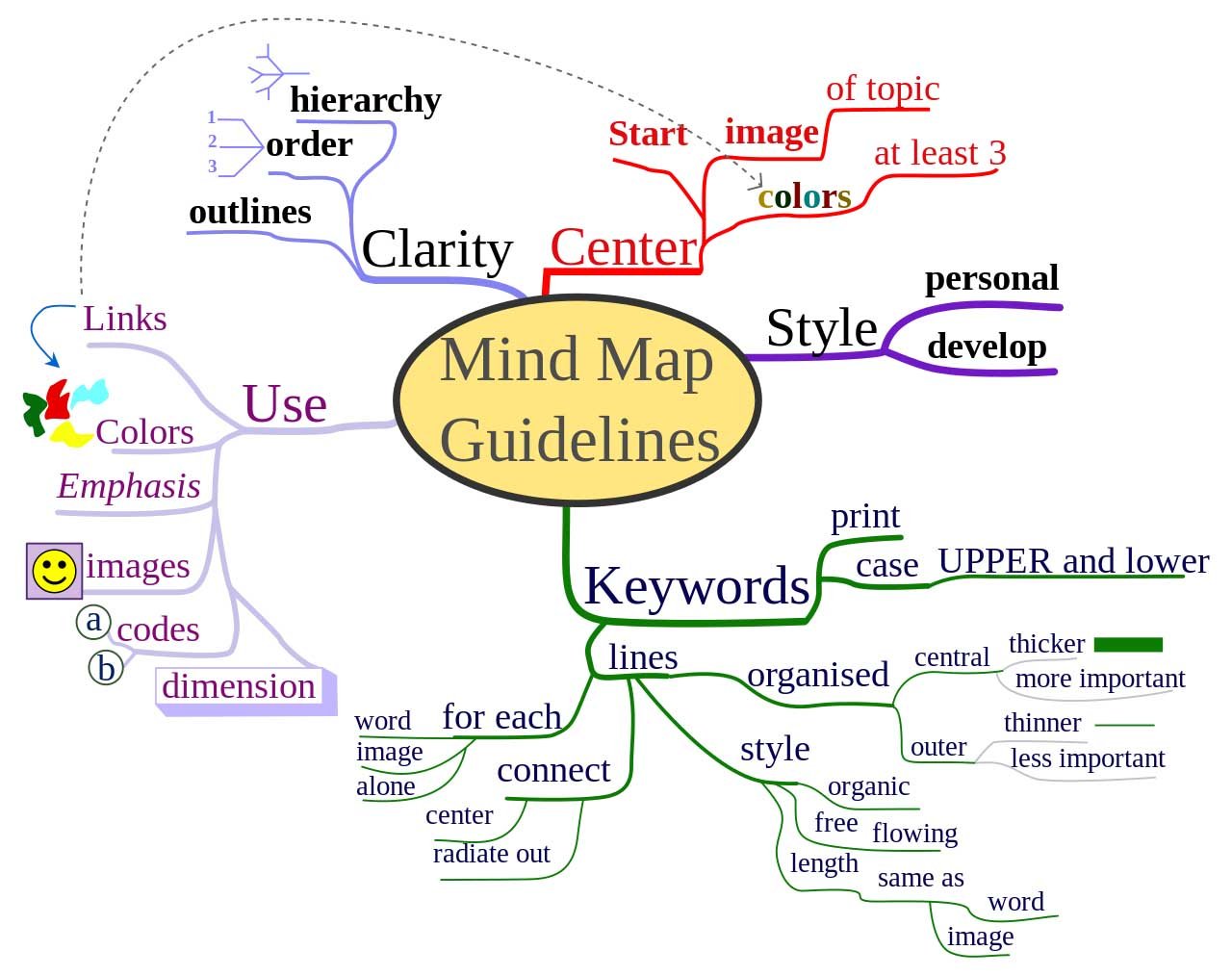

The study also suggests a method called mind mapping. This exercise helps writers access the right side of their brain, which is associated with creativity. According to the report, you begin by taking a blank sheet of paper and turning it horizontally to change the way your brain normally relates to a blank page. Then, you should quickly start writing any thoughts that come to your head surrounding your piece.

Another technique was coined by author Peter Elbow, who suggested using a technique he developed and called “loop writing”. Loop writing is simply writing all your thoughts down on the page, with no regard for conceptual biases or even grammatical correctness.

While the flow may be more of a slow trickle at first, the ideas will begin to come more freely. You do not need to adhere to any structure or rules, you should just write down whatever thoughts may come to mind. When you are finished, read back everything you wrote and try to find patterns and connections between the ideas. Draw lines connecting the corresponding ideas together. This will trigger the left side of your brain, the side that deals with logic and analysis, to begin to organize your thoughts into workable pieces.

Working with a group

In her book, Concepts in Composition: Theory and Practice in the Teaching of Writing, author Irene L. Clark suggests participating in group discussion and actively engaging in the text itself. She, like many others, also praises the power of a good brainstorming session. A writer may attempt to come up with a number of different characters, settings, or plot points.

After the writer has composed their list, it can be helpful to select one of them as a starting point and begin free writing anything that comes to mind when they think of that particular prompt. When a brain is under attack from writer’s block and becomes muddy, writing becomes a labor. Sometimes making yourself to write something, anything at all, is often very helpful in breaking through the block in creativity.

Classroom exercises

In his article mentioned earlier, Lawrence Oliver discusses similar strategies for reducing the struggle of writer’s block. His suggestions are more directed towards the educators who teach young writers to develop their writing talents. A writer can learn which side of their brain is dominant, and play to it’s strengths. Oliver believes that it can be incredibly helpful for teachers to question their students about the pieces they produce, because it puts them in a position where they are forced to think critically about their own work.

Questioning them about things such as a character’s motives, the direction of a piece of dialogue, or their choice of setting will help the student further develop their piece by opening up a new path the student may not have previously considered. Oliver goes on to stress the importance of an educator’s encouragement and support of young writers. Giving students a prompt, even something as simple as giving them one sentence and having them develop a short story from it, can help break through the block and allow students to work freely again.

Examples of single sentence prompts include:

- When I wake up, it doesn’t hit me immediately, but it doesn’t take more than a minute to remember that this will be my last day on earth.

- I told my neighbor that he would regret what he did to me someday- it looks like that day is today.

- My mother looks at me expectantly and I quickly debate in my head whether telling her my secret is a good idea or not.

While his suggestions are for professors looking to help their students, these strategies can also be applied to lone individuals. Systematically questioning your own work and working on seemingly small details can be helpful in preventing yourself from becoming stuck for too long. Prompting yourself to write freely starting from a single sentence, though difficult at first, can assist you in further developing your work.

What not to do in order to beat writer’s block

There are certainly a number of suggestions on what to do when confronted with a serious case of writer’s block. However, there are some things that you should definitely not do in an attempt to think creatively. Though experiencing a block in the creative flow is undoubtedly stressful and anxiety-inducing, the worst thing a writer could do in the face of writer’s block is continue to stress.

Writer’s block is brought on by stress in one form or another, whether it is the stress of being unproductive or the stress of writing to a certain standard. If stress is the culprit, adding more stress to the pot will simply not work. Even if the reason for your block is due to something out of your control, like a disruption in your personal life, it is best not to get worked up. The increased stress will only contribute to your writer’s block and entangle you in the vicious cycle- you stress because you cannot write but you cannot write because you are stressed.

If you should find yourself reaching a stressful point in your writing and unable to move past it, you can try one of the methods discussed above for battling writer’s block. Sometimes even walking away from your work for a little bit can be helpful. Another thing you can do is to start reading an unfamiliar book. Not only can reading something new stimulate the brain, but science proves reading can make you a better writer.

But a passionate writer should never lose heart. Remaining positive and proactive can make a significant difference in reducing the effects of writer’s block.

Forcing yourself to write when you are genuinely stuck can be counterproductive. It can be very helpful, as well, to walk away from your work for a little bit and return later to approach it with fresh eyes. However, it is important that during your break, you do something engaging. Zoning out by watching television or engaging in something similarly unproductive will not be helpful in spurring on the creative process.

Conclusion

Whether you write only because you have been assigned to, or you write for a living, you have probably experienced writer’s block in your lifetime. We are all familiar with the sinking feeling of reaching a block in your creative thoughts and being unable to push past it. Writer’s block isn’t simply the result of common mistakes made by inexperienced writers. As shown above, even the most famous names in literature have not been immune and are familiar with the struggle of being unable to initiate the creative flow.

While writers have been experiencing this for centuries and are likely to continue to do so, writer’s block does not have to be a permanent state. Hopefully, the many tips and suggestions on breaking the vicious cycle of writer’s block within this article can help you persevere as a successful writer.

If you enjoyed this article and are looking for a career in freelance writer, consider becoming an Ultius writer by submitting your application.

What is speedwriting? The solution you need to overcome writer’s block.

Works Cited

Akhtar, Salman. Comprehensive Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. Karnac Books, 2009.

Amis, Martin. The War Against Cliche: Essays and Reviews 1971-2000. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2014.

Bane, Rosanna. “The Writer’s Brain: What Neurology Tells Us about Teaching Creative Writing”. Creative Writing: Teaching Theory & Practice, vol. 2, no. 1, 2010, p. 41-50.

Cass, Dennis. “How to Get Unstuck: The Psychology of Writer’s Block”. The Literary Life, January/February 2010.

Clark, Irene L. Concepts in Composition: Theory and Practice in the Teaching of Writing. Routledge, 2011.

Cullinan, John. “Anthony Burgess, The Art of Fiction”. The Paris Review, vol. 56, no. 48, 1973.

Guilford, J.P. “Creativity”. American Psychologist, vol. 5, no. 9, 1950, p. 444-454.

Jansson, David G., and Steven M. Smith. “Design Fixation”. Institute for Innovation and Design in Engineering: Texas A&M University, vol. 12, no. 1, 1991, p. 3-11.

King, Stephen. ‘The Writing Life”. Washington Post, 1 October 2006, Web.

<http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/09/28/AR2006092801398.html>

O’Connor, Kate. “The Curious Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald”. University of Oxford. NP. Web. Accessed Jan. 02. 2017.

<http://www.writersinspire.org/content/curious-life-f-scott-fitzgerald>

Oliver Jr., Lawrence J., “Helping Students Overcome Writer’s Block.” Journal of Reading, vol. 26, no. 2, 1982, p. 162-168.

O’Neill, Michael. Percy Blythe Shelley: A Literary Life. Springer, 1989.

Rampersad, Arnold. Ralph Ellison: A Biography. Knopf, 2007.

Conrey, Sean M. and Brizee, Allen. “Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block”. Purdue Online Writing Lab. 7 Jul. 2011. Web. <https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/567/01/>

- MLA Style

- APA Style

- Chicago Style

- Turabian

Ultius, Inc. "Overcoming Writer’s Block – Psychological Causes and Scientifically Proven Solutions." Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services. Ultius Blog, 31 Jan. 2017. https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/overcoming-writers-block-psychological-causes-and-scientifically-proven-solutions.html

Copied to clipboard

Click here for more help with MLA citations.

Ultius, Inc. (2017, January 31). Overcoming Writer’s Block – Psychological Causes and Scientifically Proven Solutions. Retrieved from Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services, https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/overcoming-writers-block-psychological-causes-and-scientifically-proven-solutions.html

Copied to clipboard

Click here for more help with APA citations.

Ultius, Inc. "Overcoming Writer’s Block – Psychological Causes and Scientifically Proven Solutions." Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services. January 31, 2017 https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/overcoming-writers-block-psychological-causes-and-scientifically-proven-solutions.html.

Copied to clipboard

Click here for more help with CMS citations.

Ultius, Inc. "Overcoming Writer’s Block – Psychological Causes and Scientifically Proven Solutions." Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services. January 31, 2017 https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/overcoming-writers-block-psychological-causes-and-scientifically-proven-solutions.html.

Copied to clipboard

Click here for more help with Turabian citations.